When you deliver a speech, you are presenting much more than just a collection of words and ideas. Because you are speaking “live and in person,” your audience members will experience your speech through all five of their senses: hearing, vision, smell, taste, and touch. In some speaking situations, the speaker appeals only to the sense of hearing, more or less ignoring the other senses. The speaking event can be greatly enriched by appeals to the other senses using presentation aids.

Presentation aids are the resources beyond the speech itself that a speaker uses to enhance the message conveyed to the audience. The type of presentation aids speakers most typically use are visual aids: pictures, diagrams, charts and graphs, maps, and the like. Audible aids include musical excerpts, audio speech excerpts, and sound effects. A speaker may also use fragrance samples or food samples as olfactory (smell) or gustatory (taste) aids. Presentation aids can be three-dimensional objects, animals, and people, and they can unfold over a period of time, as in the case of a how-to demonstration.

As you can see, the range of possible presentation aids is almost infinite. However, to be effective, each presentation aid a speaker uses must be a direct, uncluttered example of a specific element of the speech. It is understandable that someone presenting a speech about Abraham Lincoln might want to include a picture of him. However, because most people already know what Lincoln looked like, the picture would not contribute much to the message (unless, perhaps, the message was specifically about the changes in Lincoln’s appearance during his time in office). Other visual artifacts are likely to deliver information more directly relevant to the speech. For example, when giving a speech about Lincoln, a speaker may use a diagram of the interior of Ford’s Theater where Lincoln was assassinated, a draft of the messy and much-edited Gettysburg Address, or a photograph of the Lincoln family. The key is that each presentation aid must directly express an idea in your speech.

Moreover, presentation aids must be used at the specific time you are presenting the ideas related to the aid. For example, if you are speaking about coral reefs and one of your supporting points is about the location of the world’s major reefs, it will make sense to display a map of these reefs while you’re talking about their location. If you display it while you are explaining what coral actually is, or after you have completed your speech, the map will not serve as a useful visual aid. In fact, it’s likely to be a distraction.

Presentation aids must also be easy to use. At a conference on organic farming, one of the authors watched as the facilitator opened the orientation session by creating a conceptual map of our concerns, using a large newsprint pad on an easel. In his shirt pocket, there were wide-tipped felt markers in several colors. As he was using the black marker to write the word “pollution,” he dropped the cap on the floor, and it rolled a few inches under the easel. When he bent over to pick up the cap, all the other markers fell out of his pocket. They rolled about too, and when he tried to retrieve them, he bumped the easel, leading the easel and newsprint pad to tumble over on top of him. The audience responded with amusement and thundering applause, but the serious tone of his speech was ruined. The next two days of the conference were punctuated with allusions to the unforgettable orientation speech. Markers falling across the floor is not how you will want your speech to be remembered.

To be effective, presentation aids must also be easy for the listeners to see and understand. In this chapter, we will present some principles and strategies to help you incorporate hardworking, effective presentation aids into your speech. We will begin by discussing the functions that a good presentation aid fulfills. Next, we will explore some of the many types of presentation aids and how best to design and utilize them. We will also describe various media that can be used for presentation aids and will conclude with tips for successful preparation and use of presentation aids in a speech.

Presentation aids are the resources beyond the speech itself that a speaker uses to enhance the message conveyed to the audience.

Why should you use presentation aids? If you have prepared and rehearsed your speech adequately, shouldn’t a good speech with a good delivery be enough to stand on its own? While it is true that impressive presentation aids will not rescue a poor speech, it is also important to recognize that a good speech can often be made better by the strategic use of presentation aids.

Presentation aids can fulfill several functions: they can serve to improve your audience’s understanding of the information you are conveying, enhance audience memory and retention of the message, add variety and interest to your speech, and enhance your credibility as a speaker. Let’s examine each of these functions.

Human communication is a complicated process that often leads to misunderstandings. If you are like most people, you can easily remember incidents when you misunderstood a message or when someone else misunderstood what you said to them. Misunderstandings happen in public speaking just as they do in everyday conversations.

One reason for misunderstandings is the fact that perception and interpretation are highly complex individual processes. Most of us have seen the image in which, depending on your perception, you see either the outline of a vase or the facial profiles of two people facing each other. These types of images show how interpretations can differ. Your presentations must be based on careful thought and preparation to maximize the likelihood that your listeners will understand the intention of your presentation.

As a speaker, one of your basic goals is to help your audience understand your message. To reduce misunderstanding, presentation aids can be used to clarify or to emphasize.

Clarification is important in a speech because if some of the information you convey is unclear, your listeners will come away puzzled or possibly even misled. Presentation aids can help clarify a message if the information is complex or if the point being made is a visual one.

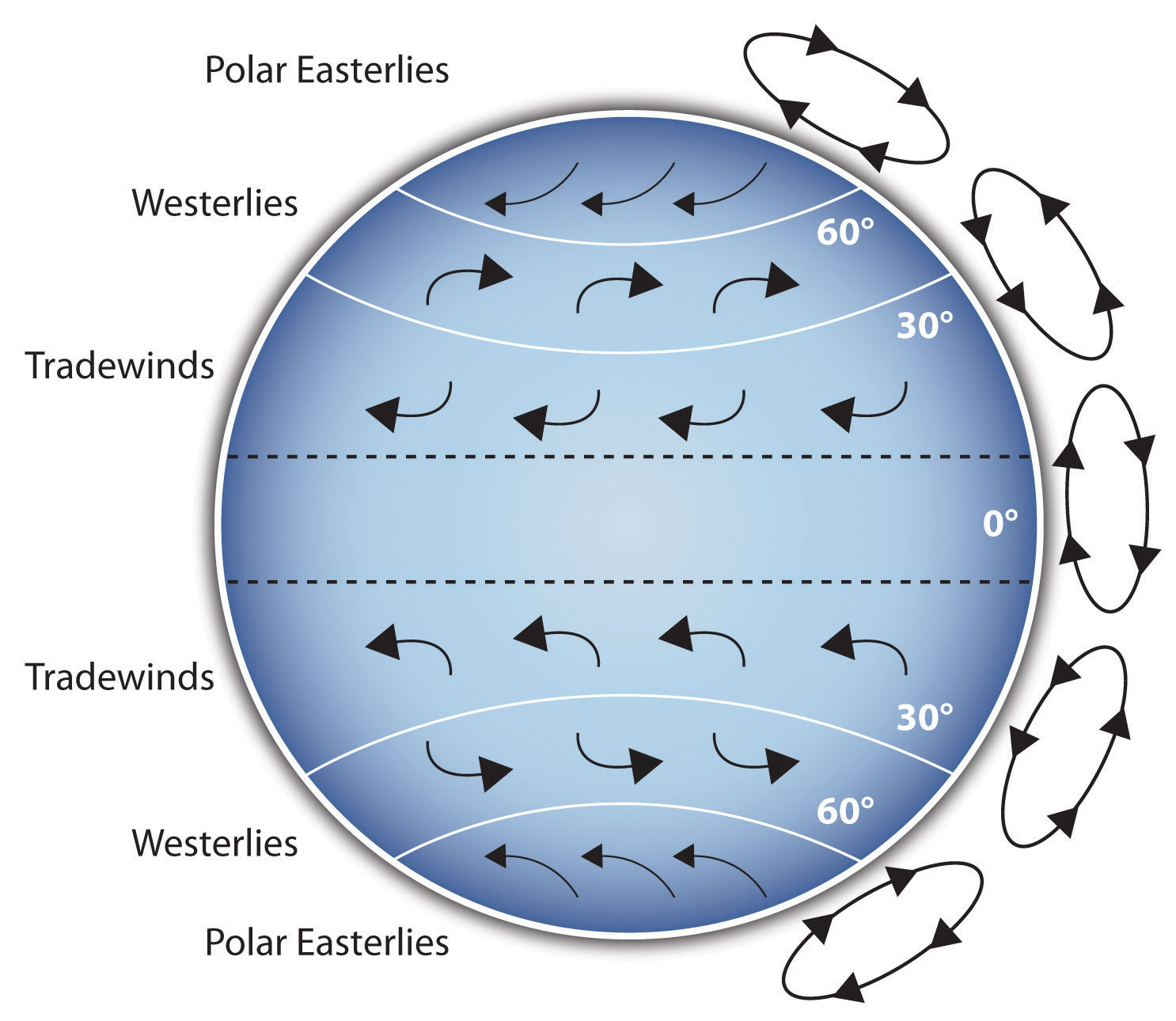

If your speech is about the impact of the Coriolis effect on tropical storms, for instance, you will have great difficulty clarifying it without a diagram because the process is a complex one. The diagram in Figure 1: The Coriolis Effect would be helpful because it shows the audience the interaction between equatorial wind patterns and wind patterns moving in other directions. The diagram allows the audience to process the information in two ways: through your verbal explanation and through the visual elements of the diagram.

Figure 1: The Coriolis Effect

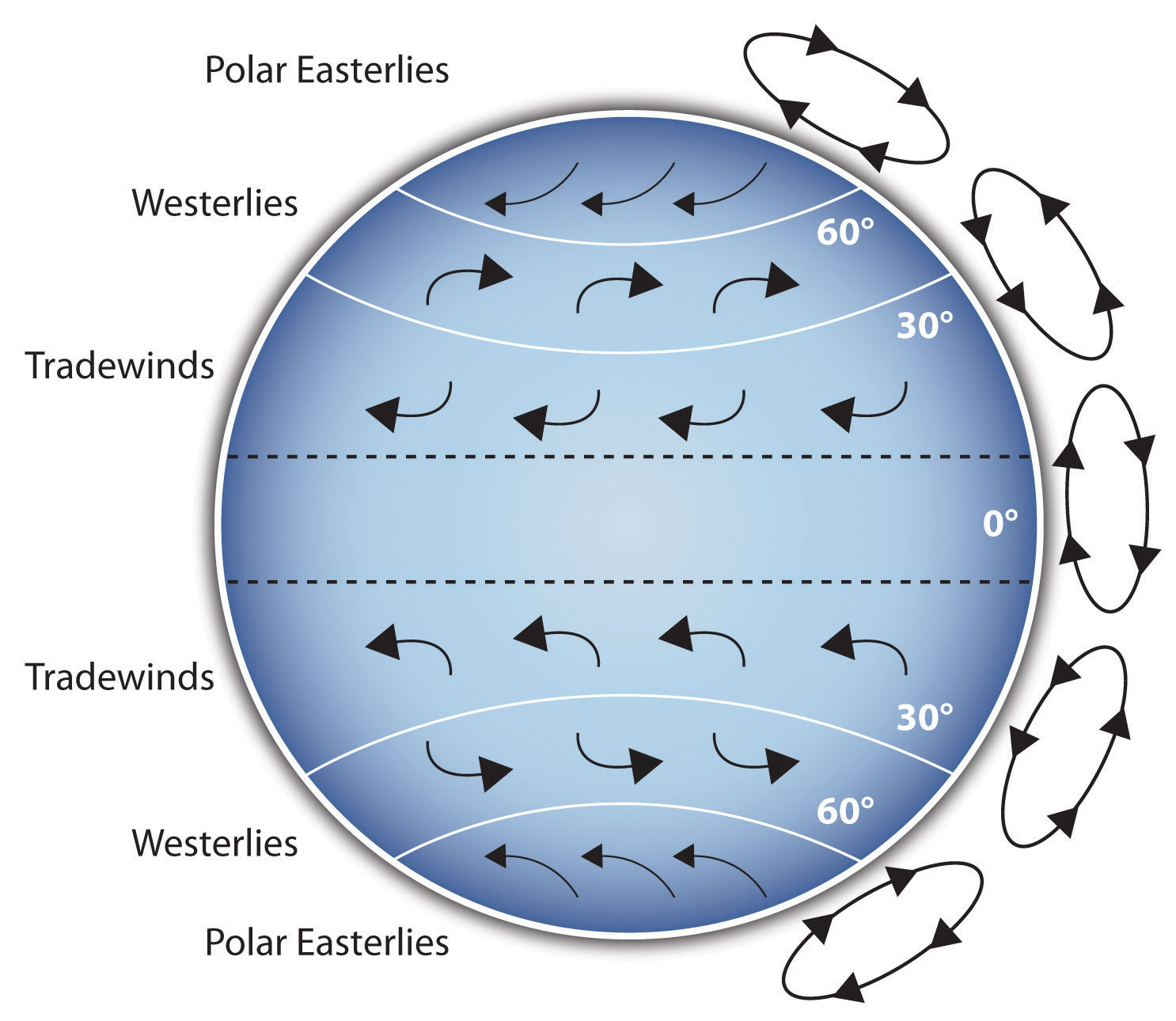

Figure 2: Model of Communication is another example of a diagram that maps out the process of human communication. In this image, you clearly have a speaker and an audience (albeit slightly abstract), with the labels of the source, channel, message, receivers, and feedback to illustrate the basic linear model of human communication.

Figure 2: Model of Communication

Another aspect of clarifying occurs when a speaker wants to visually help audience members understand a visual concept. For example, if a speaker is talking about the importance of petroglyphs in Native American culture, just describing the petroglyphs won’t completely help your audience to visualize what they look like. Instead, showing an example of a petroglyph, as in Figure 3: Petroglyph, could help your audience form a clear mental image of your intended meaning.

Figure 3: Petroglyph

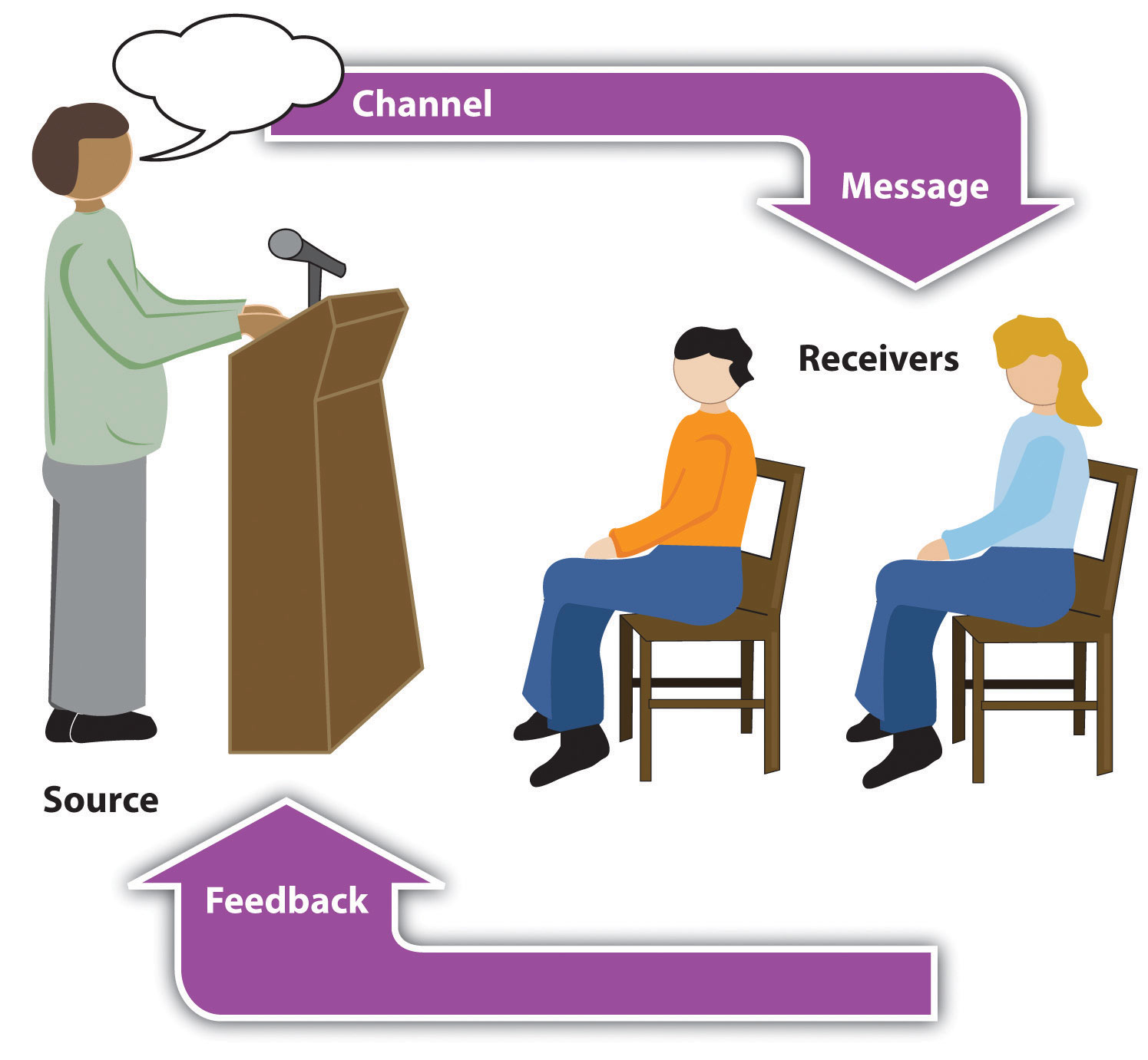

When you use a presentational aid for emphasis, you impress your listeners with the importance of an idea. In a speech on water conservation, you might try to show the environmental proportions of the resource. When you use a conceptual drawing like the one in Figure 4: Planetary Water Supply, you show that if the world water supply were equal to ten gallons, only ten drops would be available and potable for human or household consumption. This drawing is effective because it emphasizes the scarcity of useful water and draws attention to this important information in your speech.

Figure 4 : Planetary Water Supply

Another way to visually emphasize information in your speech is to zoom in on a specific aspect of interest within your speech. In Figure 5: Chinese Lettering Amplified, we see a visual aid used in a speech on the importance of various parts of Chinese characters. On the left side of the visual aid, we see how the characters all fit together, with an emphasized version of a single character on the right.

Figure 5: Chinese Lettering Amplified

The second function that presentation aids can serve is to increase the audience’s chances of remembering your speech. A 1996 article by the US Department of Labor summarized research on how people learn and remember. The authors found that “83% of human learning occurs visually, and the remaining 17% through the other senses—11% through hearing, 3.5% through smell, 1% through taste, and 1.5% through touch” (United States Department of Labor, 1996). Mostly, people learn through seeing things, so the visual component of learning is very important. The article goes on to note that information stored in long-term memory is also affected by how we initially learn the material. In a study of memory, learners were asked to recall information after a three day period. The researchers found that they retained 10 percent of what they heard from an oral presentation, 35 percent from a visual presentation, and 65 percent from a visual and oral presentation (Lockard & Sidowski, 1961). It’s amazing to see how the combined effect of both the visual and oral components can contribute to long-term memory.

For this reason, exposure to a visual image can serve as a memory aid to your listeners. When your graphic images deliver information effectively, and when your listeners understand them clearly, audience members are likely to remember your message long after your speech is over.

Moreover, people can remember information that is presented in sequential steps more easily than if that information is presented in an unorganized pattern. When you use a presentation aid to display the organization of your speech, you will help your listeners to observe, follow, and remember the sequence of information you conveyed to them. This organization is why some instructors display a lecture outline for their students to follow during class.

An added plus of using presentation aids is that they can boost your memory while you are speaking. Using your presentation aids while you rehearse your speech will familiarize you with the association between a given place in your speech and the presentation aid that accompanies that material. For example, if you are giving an informative speech about diamonds, you might plan to display a sequence of slides illustrating the most popular diamond shapes: brilliant, marquise, emerald, and so on. As you finish describing one shape and advance to the next slide, seeing the next diamond shape will help you remember the information about it that you are going to deliver.

The third function of presentation aids is to make your speech more interesting. While it is true that a good speech and a well-rehearsed delivery will already include variety in several aspects of the presentation, in many cases, a speech can be made even more interesting by the use of well-chosen presentation aids.

For example, you may have prepared a great speech to inform a group of gardeners about several new varieties of roses suitable for growing in your local area. Although your listeners will undoubtedly understand and remember your message very well without any presentation aids, wouldn’t your speech have greater impact if you accompanied your remarks with a picture of each rose? You can imagine that your audience would be even more enthralled if you could display an actual flower of each variety in a bud vase.

Similarly, if you were speaking to a group of gourmet cooks about Indian spices, you might want to provide tiny samples of spices that they could smell and taste during your speech. Taste researcher Linda Bartoshuk has given presentations in which audience members receive small pieces of fruit and are asked to taste them at certain points during the speech (Association for Psychological Science, 2011).

Presentation aids alone will not be enough to create a professional image. As we mentioned earlier, impressive presentation aids will not rescue a poor speech. However, even if you give a good speech, you run the risk of appearing unprofessional if your presentation aids are poorly executed. Meaning, that in addition to containing important information, your presentation aids must be clear, clean, uncluttered, organized, and large enough for the audience to see and interpret correctly.

Misspellings and poorly designed presentation aids can damage your credibility as a speaker. Conversely, a high-quality presentation will contribute to your professional image. Additionally, make sure that you give proper credit to the source of any presentation aids that you take from other sources. Using a statistical chart or a map without proper credit will detract from your credibility, just as using a quotation in your speech without credit would.

If you focus your efforts on producing presentation aids that contribute effectively to your meaning, and look professional and are well handled, your audience will most likely appreciate your efforts and pay close attention to your message. That attention will help them learn or understand your topic in a new way and will thus help the audience see you as a knowledgeable, competent, credible speaker.

As we saw in the example of the presentation at the organic farming conference, using presentation aids can be risky. However, with a little forethought and adequate practice, you can choose presentation aids that enhance your message and boost your professional appearance in front of an audience.

One principle to keep in mind is to use only as many presentation aids as necessary to present your message or to fulfill your classroom assignment. Although the maxim “less is more” may sound like a cliché, it really does apply in this instance. The technical sophistication of your presentation aids should never overshadow your speech.

Another important consideration is technology. Keep your presentation aids within the limits of the working technology available to you. Whether or not your classroom technology works on the day of your speech, you will still have to present. What will you do if the computer file containing your slides is corrupted? What will you do if the easel is broken? What if you had counted on stacking your visuals on a table that disappears right when you need it? You must be prepared to adapt to an uncomfortable and scary situation. These scenarios are why we urge students to go to the classroom at least fifteen minutes ahead of time to test the equipment and ascertain the condition of things they’re planning to use. As the speaker, you are responsible for arranging the items you need to make your presentation aids work as intended. Carry a roll of duct tape so you can display your poster even if the easel is gone. Find an extra chair if your table has disappeared. Test the computer setup, and have an alternative plan prepared in case there is some glitch that prevents your computer-based presentation aids from being usable. The more sophisticated the equipment is, the more prepared you should be with an alternative, even in a “smart classroom.”

More important than the method of delivery is the audience’s ability to see and understand the presentation aid. It must deliver clear information, and it must not distract from the message. Avoid overly elaborate presentation aids because they can distract the audience’s attention from your message. Instead, simplify as much as possible, emphasizing the information you want your audience to understand.

Another thing to remember is that presentation aids do not “speak for themselves.” When you display a visual aid, you should explain what it shows, pointing out and naming the most important features. If you use an audio aid, such as a musical excerpt, you need to tell your audience a specific thing to listen for. Similarly, if you use a video clip, it is up to you as the speaker to point out the characteristics of the video that support the point you are making.

Although there are many useful presentation tools, you should not attempt to use every one of these tools in a single speech. Your presentation aids should be designed to look like a coherent set. For instance, if you decide to use three slides and a poster, all four of these visual aids should make use of the same type font and basic design.

Now that we’ve explored some basic hints for preparing visual aids, let’s look at the most common types of visual aids: charts, graphs, representations, objects/models, and people.

A chart is a graphical representation of data (often numerical) or a sketch representing an ordered process. Whether you create your charts, or do research to find charts that already exist, it is important for them to exactly match the specific purpose in your speech. In the rest of this section, we’re going to explore three common types of charts: statistical charts, sequence-of-steps chart, and decision trees.

For most audiences, statistical presentations must be kept as simple as possible, and they must be explained. Unless you are familiar with statistics, a chart may be very confusing. When visually displaying information from a quantitative study, you need to make sure that you understand the material and can successfully explain how one should interpret the data. If you are unsure about the data yourself, then you should probably not use this type of information. Figure 6: Effects of Smoking on Different Body Systems is surely an example of a visual aid that, although it delivers a limited kind of information, does not speak for itself.

Figure 6: Effects of Smoking on Different Body Systems