Lazy lawyers tend to make discovery requests formulaic. They have “stock” or “off-the-shelf” discovery requests they use for almost every case. This make make things easy, but it also means not exercising due diligence when it comes to preparing a case.

Yes, there will always be a few standard issues to be covered in many lawsuits, but in general, it’s poor form and not something you want to do. That’s why last year I touched on how to write better requests for admissions.

Today, let’s tackle requests for production (RFPs).

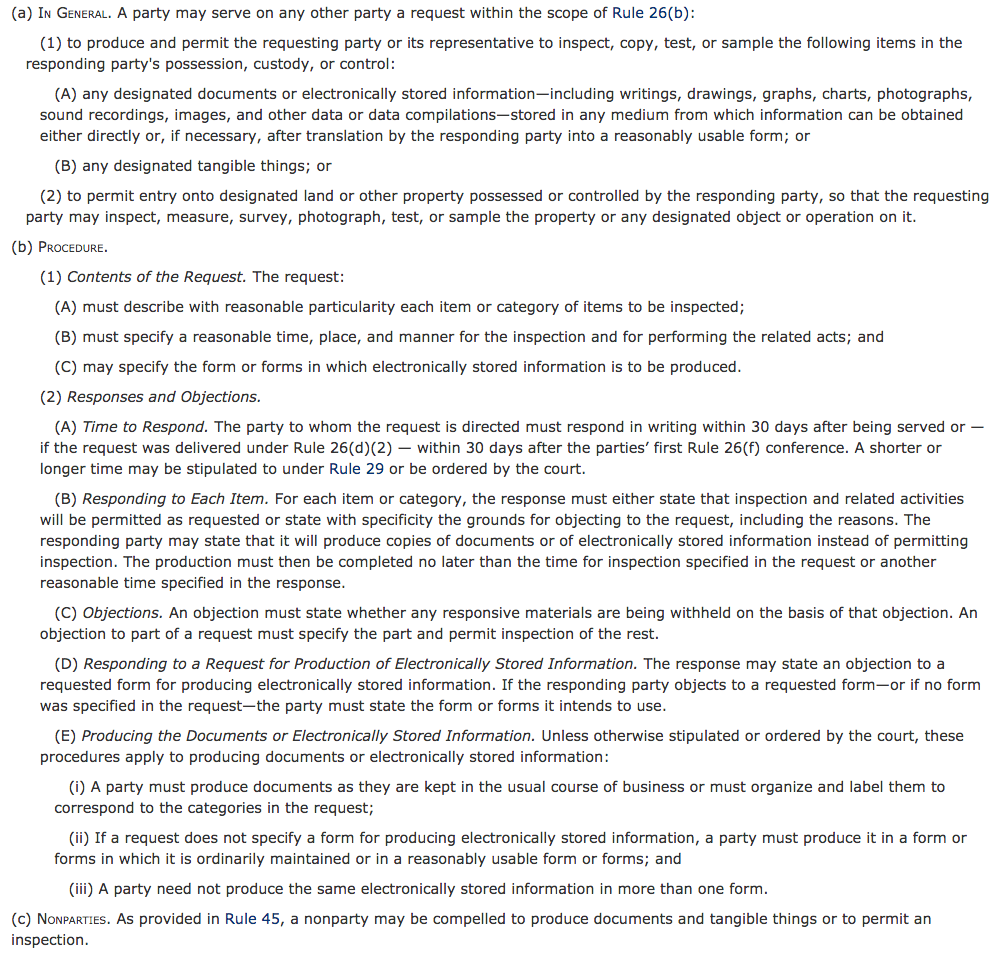

The rules for RFPs vary from jurisdiction-to-jurisdiction, so let’s look at FRCP Rule 34 as an example.

Click for large version.

So what we’re looking at is the methodology by which one party can request to inspect, copy, test, or sample documents, or electronically stored information, stored in any medium. With that in mind, let’s look at some general guidelines for how to do this better.

Step one: Read the local rules.

Step two: Go back and read the local rules again.

Jurisdictions often have their own rules regarding the timing and form of RFPs. You absolutely cannot assume that every jurisdiction follows the FRCP as a model. Be sure to look for:

When you sit down to draft RFPs, you likely have a pretty good idea of what the case is about, regardless of what side of the aisle you’re on. Slip and fall? Boundary line dispute? Corporate contract dispute? Knowing the case and general background should help you develop the theory and theme of the case. Despite being only in the initial discovery stages, you should already have the end of the case in mind.

You shouldn’t be drafting RFPs as a perfunctory, routine measure of going through the motions, but crafting them in such a way that they will provide you relevant evidence that you can use at trial.

As long as you have the end of the case in mind, meaning you’re preparing for a long slog, you should agree with opposing counsel on a bate stamping scheme. This used to be done manually (I did it when I was a law clerk), but now is often handled in by the discovery software platform you’re using. Or it can be done by an office copier. Even seemingly simple cases often involve thousands of pages of documents. Save everyone the headache and agree to a common numbering system.

Accompanying your RFPs (although likely beforehand), should be a litigation hold letter to any and all parties upon whom you might serve discovery requests. This is a notice to any parties that information they contain may be relevant to a lawsuit and special care needs to be taken to ensure that it is preserved and untampered with. This is especially important considering that many companies now have document destruction policies in which emails, memos, files, etc are destroyed on a regular basis.

You should also request a privilege log along with your other RFPs. A party may claim that one or more of the documents you are requesting are subject to attorney–client privilege, work product doctrine, or some other privilege. If that is the case, you can rely on FRCP Rule 26(b)(5)(A) (or equivalent local rule) which states state a party declining to produce documents on privilege grounds must:

(i) expressly make the claim; and

(ii) describe the nature of the documents, communications, or tangible things not produced or disclosed—and do so in a manner that, without revealing information itself privileged or protected, will enable other parties to assess the claim.

In today’s digital age, the form in which documents are produced can be just as important as what is produced. DOC, PDF, PPT, XLX, TIFF, BAT, etc. There are all sorts of formats for the storage of data. The specific format in which the data is stored can sometimes provide additional information that might not be apparent if it were presented as a plain text or printed out. It’s important that you request documents in their native format.

Along the lines of form of production, is metadata – “data about other data.” When you draft a document in a word processor, it doesn’t just save the text you’ve typed, it may save: all the formatting information, the time it was saved, the name registered to the software used to draft it, number of edits, persons who have had control of the document, etc. This information can be very important in certain cases.

Given that critical information is often stored in metadata, many law firms will employ software to “scrub” any metadata from production. If you don’t request it, you likely won’t get it.

It’s difficult to give general advice regarding RFPs because by their very nature, they are case dependent. You likely don’t need to request a birth certificate in a boundary line dispute. You need to request anything that is relevant or would likely lead to the discovery of relevant information. Which is where things get tricky.

If you’re too broad with your requests, a party might just send you mountains of documents, very little of it relevant. They’ll drown you in production. If you’re too narrow, they might not produce all the documents you need because they’re wriggling around your request.

So your requests need to be focused in scope, as well as comprehensive. It’s a fine line to walk. If you’re new to drafting RFPs, there are a few places you can look for guidance:

RFPs are an incredibly important part of the litigation process. Don’t be lazy and use stock requests for your cases. When it comes time to draft RFPs, don’t think of it as a boring, routine task. Instead, re-frame it as an opportunity to improve and develop your writing and analytical skills.

Looking for more ways to improve your legal writing? I’ve compiled some my best advice on legal writing into one comprehensive, easy-to-follow guide. It can be yours – free. Just sign up below.